The Future of Mexican Basketball Has Arrived in the Form of an Inferno

This season, I watched the LNBP transform with the addition of los Diablos Rojos del México

You’ve probably never been to Gimnasio Universitario de la Unidad Deportiva. Unless, of course, you’re a god-tier hoops sicko and have been to Xalapa — the verdant, bohemian capital of Veracruz along the Gulf of Mexico, most notably of jalapeño and La Bamba fame — to partake in the Xalapeño basketball tradition.

The humble Gimnasio, which structurally resembles a basic college gym back in the United States, is tucked away in an unkempt jungle, surrounded by brackish lake waters and centuries-old stone. Everything looks worn down here, where ongoing rainstorms and a dense humidity press up against your comfort like an unrelenting full-court defender on the hottest of summer nights. But there’s more to this dilapidated city — and this country’s love of basketball — than it ever gets credit for. And it’s all on display inside that gym.

Known locally as El Nido — or, The Nest — it’s the singularly most cathartic basketball experience I’ve found in Latin America. A holy house of hoops, of sorts. And it’s precisely where 2,638 impassioned Mexican fans gathered for the closing game of the 2024 Liga Nacional de Baloncesto Profesional’s Gran Final this past December between the Halcones de Xalapa (a four-time champion legacy franchise in the pro Mexican league) and Diablos Rojos del México (an upstart expansion team in their debut season).

My reader, when I tell you that the arena was swaying from tip-off to buzzer, I don’t only mean that figuratively. This is where diehard basketball zealots converged as if embarking on a lifelong pilgrimage. Where the tightly-sectioned bleachers were so packed with loud, pulsating bodies that someone’s knee continually brushed the back of my head while an employed beer runner somehow careened himself through the tightest spaces in a small sea of jersey-wearing fanatics, simply to deliver a michelada (a national treasure of a beverage consisting of beer mixed with Clamato juice, Worcestershire sauce, hot sauce and chamoy). If that sounds like overload, it is.

Three rows behind the baseline, on the opposite side of where coaches barked at players and players barked at one another, is where I witnessed the Diablos Rojos (also known as los pingos, or little devils) cap off their historic inaugural campaign as the LNBP’s triumphant newcomers — becoming first-time champions.

I watched, somewhat bitterly as the son of Xalapeños, while Luciano Gonzalez, an Argentinian hooper, climbed atop the rim and sat there post-game, overlooking the court as a visiting player while his legs dangled in victory and stressed security personnel called for him to get down from below.

I saw Avry Holmes, an Oregon-born point guard who once balled in the NCAA at the University of San Francisco and G League with the Santa Cruz Warriors, receive the MVP de la final trophy.

I took note of those who celebrated (namely, the large section of traveling Diablos Rojos fans wearing all-red behind the pingos’ bench) and those who didn’t (Halcones fans, staff and players, an underdog city and team filled with scrappy veterans, a few of whom had unfortunately fallen to injury while sprinting for the national crown).

Above all, I sensed a burgeoning moment in Mexican sports culture — and in the people’s loving embrace of “el deporte rafaga,” otherwise known as basketball.

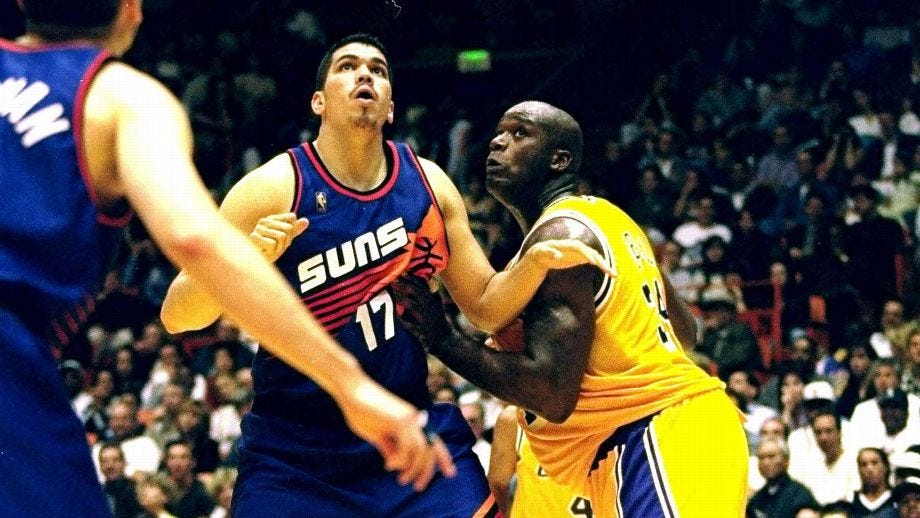

The NBA crossed the border for the first time in 1992 in an attempt to export the game to an overwhelmingly Spanish-speaking fanbase. Nearly a decade later, the LNBP was founded (circa 2000) and has been a lower-rung option for Mexican aspirationalists and international nylon mercenaries who haven’t, for one reason or another, made it elsewhere.

The league has historically attracted a mix of hopeful prospects, rogue pariahs and late-career runaways from abroad, including Dennis Rodman, who formerly suited up with national powerhouse Fuerza de Regia in 2004, and LiAngelo Ball, who as recently as last season donned an Astros de Jalisco uniform. Other noteworthy, if not peculiar, LNBP imports from the NBA have included Robert “The Tractor” Traylor, Jamario Moon, Juan Toscano-Anderson, and Kenneth “The Manimal” Faried. To date, only two LNBP players, both Mexican-born — point guard Jorge Gutierrez and big man Gustavo Ayón — have made the reverse migration into the NBA.

As a result of its lacking star power, basketball in Mexico doesn't quite hold the same weight as fútbol. Not yet, at least. It’s a relatively new sport, after all. And it certainly doesn’t have the historical cache or pastime glory of baseball.

That’s where the Diablos Rojos have merged the two. Despite winning their first LNBP chip in 2024, the franchise is no stranger to dynastic winning. Dating back to 1940, the Diablos Rojos have established themselves as the New York Yankees of the Mexican baseball empire. With 17 league titles (and recent exhibition victories against the actual Yankees during two games that aired as part of ESPN’s MLB coverage), the pingos represent the ultimate apex of béisbol in Mexico.

When the team announced their expansion into the country’s pro basketball circuit less than a year ago, it surprised and excited, if not startled, the throngs of hoop heads throughout La República Mexicana. Imagine that the New York Yankees suddenly launched a well-funded superteam in another, less competitive sport and recruited many of that league’s top players to join them. That’s kind of what the Diablos Rojos did.

That’s not to say the Diablos Rojos are merely poaching talent. They’ve rightfully built up the finest roster in the LNBP, something that their historic baseball franchise’s deep pockets and invested owners could afford them. Even then, the team has executed their vision flawlessly and helped to revive basketball in the Aztec capital. With General Manager Nick Lagios, formerly of the Mexico City Capitanes and South Bay Lakers (pre-Bronny James, I might add), leading the helm, they’ve equipped a versatile cast of well-rounded, proven basketballers. And they’ve also poured into Mexico’s basketball community with free events, community courts, streetwear collabs and upcoming youth camps. It’s something the country is in want of.

The team is currently housed at El Gimnasio Olímpico Juan de la Barrera on Mexico City’s infinitely sprawling southern end. The arena is outdated, to put it nicely — a historic remnant built for the 1968 Olympics, which still seems to carry the scent of faded sweat from that era. Attending a game there feels like warping back in time, a sensation that is at once cool and strange for anyone who has been numbed by high-tech, capitalist-fueled circuses like San Francisco's Chase Center (home of the Golden State Warriors and Valkyries) or Brookyln’s Barclays Center (home of the Nets and New York Liberty). Nah, this isn’t that. Not even close. And perhaps because of that chasmic distance — physically, but also infrastructurally, culturally and economically — you can enjoy the purity of unadulterated hoops.

In the LNBP — and I imagine the global basketball community at-large — there are far less foul baiters and free throw merchants (hello James Harden and yes, you too, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander). There’s no panopticon-like loom of face-recognizing cameras and flashing mega screens (I haven’t been to Intuit Dome, the newly minted home of the Los Angeles Clippers, yet but god damn, I imagine it’s at least reminiscent of some failed, dystopian future, where the main attraction at a basketball game isn’t even the basketball being played).

In Mexico, basketball — and really, life itself — often gets stripped down to the literal fundamentals, the basics. Whatever isn’t absolutely necessary doesn’t intervene. And that’s part of what made following the Diablos Rojos’ run so entertaining for me, while being in Mexico to understand its day-to-day context. A team that was built for success, in a league that could use it. For a country that is more ready than ever to run it back.